Murakami Against Notebooks

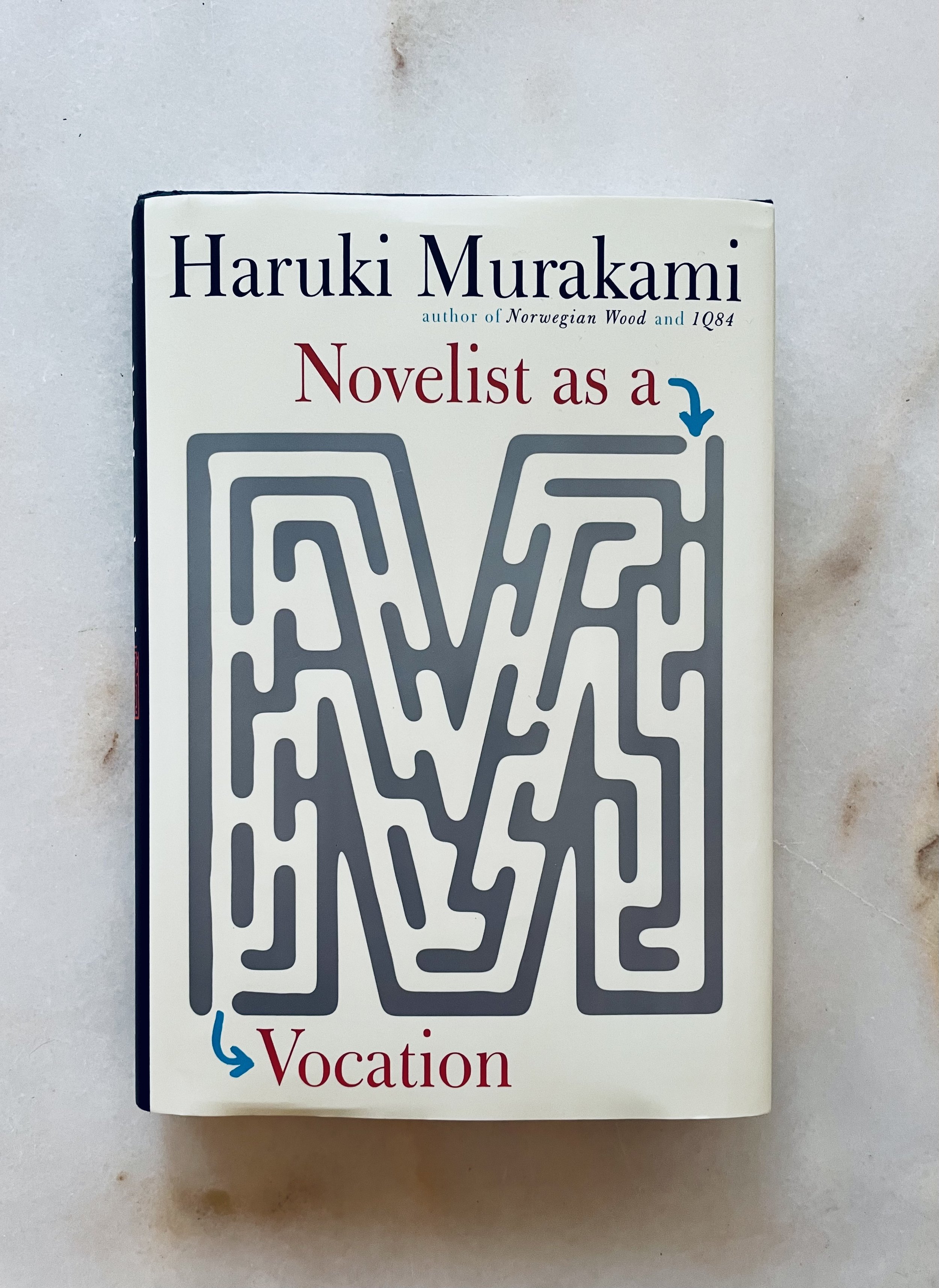

Adam on some upsetting commentary in Haruki Murakami’s Novelist as a Vocation.

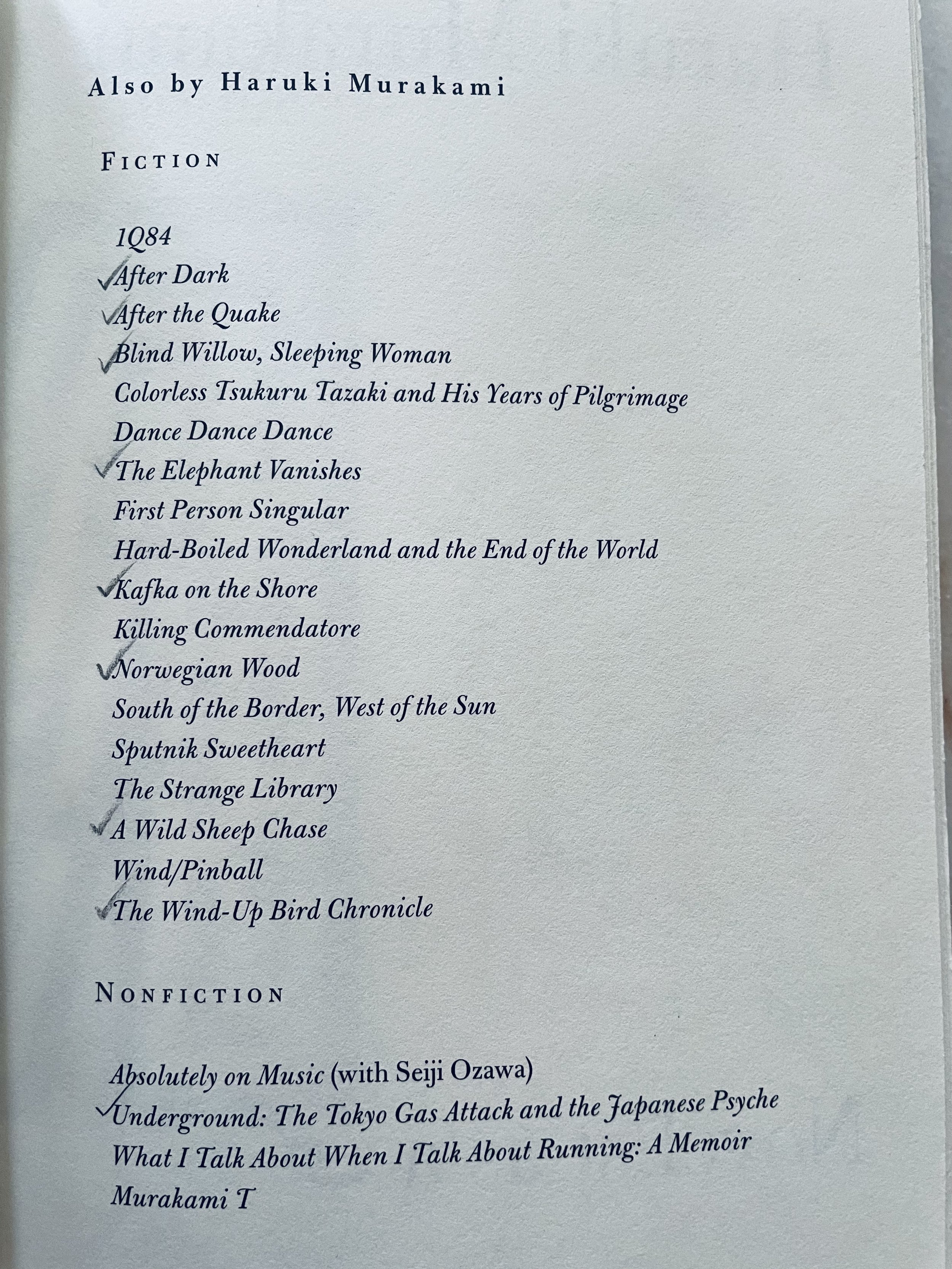

This essay collection on writing is the tenth Murakami book I’ve read and I believe it’s my least favorite. (I can’t quite remember After Dark but I think it was middling.) However, it’s also the Murakami book I’m most likely to reread. There was some wisdom in those pages and I may have missed a lot of it because I was distracted by Murakami’s defensiveness and by the redundancies across the essays.

In the style of the book, let me insist that I don’t give much thought to Murakami’s stance against notebooks and the passage that follows didn’t affect my opinion of the book whatsoever:

Of course, realistically, it is impossible to retain everything. There is a limit to how much our memory can hold. Thus, we need a minimal kind of information-processing system to reduce the amount.

In most cases, I try to fix a few telling details about the event (or the person, or the scene) in my mind. Since it is hard to recall (or, having attempted to remember, easy to forget) the whole picture, it is best to try to extract specific features in a form that can be easily held for safekeeping. This is what I mean by a minimal system.

What sorts of features? They tend to be those striking details that make you sit up straight, that fix themselves in your mind. Ide-ally, those things that can't be explained away. It is best if they are illogical, or counter the flow of events in a subtle way, or tempt you to question them, or suggest some kind of mystery. You gather these bits, affix a simple label (place, time, situation) and mentally file them away in your personal chest of drawers. It is possible, of course, to jot them down on a notepad or something of the sort, but I prefer to trust my mind. It's a real pain to carry a pad around, and I have found that once I have jotted something down I tend to relax and forget it. IfI toss the bits into my mind, on the other hand, what needs to be remembered stays while the rest fades into oblivion. I like to leave things to this process of natural selection.

This reminds me of an anecdote I'm fond of. When Paul Valéry was interviewing Albert Einstein, he asked the great scientist, "Do you carry a notebook around to record your ideas?" Einstein was an unflappable man, but this question clearly unnerved him. "No," he answered. "There's no need for that. You see I rarely have new ideas."

Come to think of it, there have been very few situations when I wished I had a notepad on me. Something truly important is not that easy to forget once you've entrusted it to your memory.

Murakami is not alone in his upsetting opinions on Take Note’s raison d'etre. Here’s George Saunders from his Substack in July 2022: “I don’t keep notebooks or journals of ideas or images or phrases or anything like that. My assumption is that if something wants and needs to show up in a story of mine, I’ll remember it, or even misremember it, and it will force its way in.”